The Banyan Tree: Untangling Cambodian History

Part Three: Toppling the Past

Throughout Cambodia the announcement of the government's surrender was met with relief. The fear, hunger, and exhaustion that had characterized life during wartime would at last be over. In Phnom Penh, particularly, the news was seen as cause for jubilation. The population of the city, about 600,000 before the war, had swollen to roughly two million with the constant flow of refugees generated by the war. For the refugees in particular, living conditions had been horrid. Many had no jobs; they lived in fetid camps, suffering from malnutrition and disease as the Khmer Rouge rained rockets and artillery fire into their midst. Now, crowds lined the streets, hailing their liberators.

The victorious soldiers did not share the sense of joy. Grim and unsmiling, still weary from battle, they made their way toward the center of the city. Having consolidated their positions, they immediately issued an order to the population: Evacuate the city.

Under the pretense that the Americans were going to bomb the city, the Khmer Rouge forced the bewildered population out into the streets. In many cases entire families were given only ten minutes to prepare for what they were told would be a three-day journey. The same scenario was played out in nearly all of the country's major cities and towns. No one was exempted; even hospitals were emptied. Patients staggered into the streets, their wounds untreated; families pushed along their loved ones, still strapped in their beds, bottles of blood and plasma held aloft in a desperate bid to fight off death. Doctors performing surgery were ordered at gunpoint to abandon their patients. Stragglers and those who refused to obey were often executed on the spot. The roads out of the cities were clogged with the exodus.The stocks of food and water accumulated for the refugees were inadequate; many succumbed to heat and exhaustion, with infants, the old, and the sick the first to die. Their relatives were forced to leave the bodies at the roadside. (

Time Magazine's article describing the evacuation can be seen by clicking here.) All in all, it is estimated that some 20,000 people died in the evacuation.

Khmer society was about to be re-invented. The Khmer Rouge proclaimed it to be "Year Zero." Immediately upon the surrender of the republican government, Pol Pot put forth an eight-point program:

1. Evacuate people from all towns.

2. Abolish all markets.

3. Abolish Lon Nol regime currency, and withhold the revolutionary currency that had been printed.

4. Defrock all Buddhist monks, and put them to work growing rice.

5. Execute all leaders of the Lon Nol regime beginning with the top leaders.

6. Establish high-level cooperatives throughout the country, with communal eating.

7. Expel the entire Vietnamese minority population.

8. Dispatch troops to the borders, particularly the Vietnamese border.

As the people made their way out of the cities and into the countryside, it became clear that the Khmer Rouge did not intend to allow them to return. Evacuees were ordered to write their biographies, explaining who they were and what type of work they had done under the old regime. The Khmer Rouge were not looking for technical expertise. They were looking for enemies.

High officials of the deposed government, including Prince Sirik Matak and Premier Long Boret, were executed immediately. Military officers -- generally all those above the rank of lieutenant -- were also executed. In many cases their families were killed as well.

Pol Pot's goal was to transform Cambodia into a completely self-sufficient agrarian communist state. The revolution justified everything; human life was expendable. A Khmer Rouge saying made the point clearly: "To preserve you is no gain, to destroy you is no loss."

Though the Khmer Rouge claimed that their revolution tore down class barriers and made everyone equal, in practice the new system created two very distinct classes: "old people" and "new people." The old people were rural people who had come under the control of the Khmer Rouge before the end of the war; new people were the city dwellers who had been evacuated from the cities after April 17. The new people were viewed with hatred and suspicion by the Khmer Rouge.

Khmer Rouge leaders were obsessed with the idea that their revolution be "pure." This absolutism was made manifest in many ways. With no markets and currency, the population was entirely dependent upon "Angkar" -- the organization -- for their needs. Books and all printed materials were forbidden. Virtually all private property was banned; except for clothing and a handful of personal effects, everything was the property of the state. Communism became the new national "religion"; monks were defrocked or even executed, and Buddhism was outlawed. No travel was allowed without expressed permission from Angkar. A curtain of darkness enveloped Cambodia; the outside world vanished beyond a border sown with mines and armed guards. Even Prince Sihanouk was uncertain about what was happening inside the country; the Khmer Rouge kept him in Beijing until December 1975, insisting that they were not yet ready for his return. When he did finally return, he became for all intents and purposes a prisoner, confined within the royal palace in the virtually deserted capital.

Within Cambodia, conditions varied widely from region to region. Some areas had been decimated by the war, while others had been spared the worst of the fighting. New people sent to relatively undamaged areas were fortunate: others were deported to virgin forest, where they were first ordered to build their own shelter, then to clear the land and plant rice. Conditions also varied depending on the manner in which local cadres chose to implement the central government's decrees. Not all of the Khmer Rouge surrendered their humanity to the revolution, and they tempered their orders with a sense of realism and mercy.

Generally, however, life under the Khmer Rouge did follow certain patterns. The cultivation of rice -- for centuries the foundation of Khmer civilization -- was the cornerstone of the communists' vision for the future. A propaganda slogan stated the premise clearly: "With rifles in one hand and hoes in the other, our workers, peasants, and revolutionary armed forces are striving grandly to build democratic Kampuchea."

Typically, men and women were organized into separate work brigades, and families were often split up as members were sent to work in different areas. In most areas, "schooling" (more accurately: indoctrination) was available only for very young children; children as young as six were assigned to "weak strength" work groups which also included the elderly. The weak strength groups performed such tasks as collecting manure, tending small gardens, or raising chickens. The "full strength" groups did the heavy work: digging canals and reservoirs, building dikes, logging, planting and harvesting the rice fields. They often worked from sunup to sundown, or even well into the night if there was enough moonlight, or if they had not met their work quota. Most areas followed a schedule of ten days of work, then one day of rest. They toiled in identical all-black clothing; expressions of individuality were not tolerated.

The idea that the people of Cambodia could have any use beyond that of a draft animal seemed to have never occurred to the Khmer Rouge. Anyone who offered advice to the Khmer Rouge was implicitly suggesting that Angkar's plan could be improved upon, and that perhaps Angkar was not infallible. Such a suggestion could easily lead to death. The Khmer Rouge saw intelligence not as a virtue, but as a threat. In many areas, educated persons were marked for execution as enemies of the state; many "new people" would later attribute their survival to having hidden their intelligence. College students, teachers, and doctors in particular were singled out as targets. Of approximately 270 doctors who remained in Cambodia after 1975, only about 40 survived Pol Pot's reign.

Many other groups were also at risk. Former republican soldiers were often executed, along with their families. Civil servants and members of ethnic minorities, too, often fell victim to the violence. As many as 100,000 ethnic Vietnamese were executed, and about 225,000 ethnic Chinese and 90,000 Chams are believed to have died of disease, starvation, or execution. Publicly speaking a language other than Khmer was punishable by death.

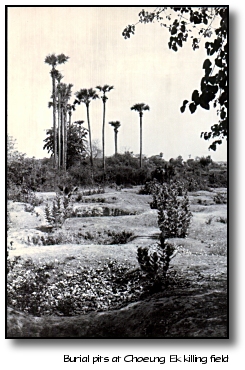

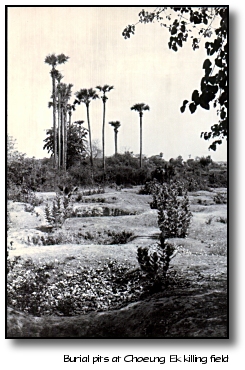

Executions were carried out in a number of different ways. Often victims were taken away to "killing fields" where they were forced to kneel in front of trenches before being killed by a blow to the head with a pickaxe or shovel. At times large groups of people were shot together; other individuals were suffocated by a plastic bag tied over their heads. Executions were also sometimes performed publicly. Some victims were beaten to death; others were disemboweled, and their livers were cooked and eaten by their killers. Whole families were often killed for the minor infractions of a single person. The Khmer Rouge did not want to leave surviving relatives who might harbor a grudge against Angkar. At times, the methods employed matched the darkest propaganda of wars gone by: Infants were smashed against trees, or thrown into the air and impaled on bayonets or bamboo stakes.

Nowhere was the brutality of the Khmer Rouge more clearly exemplified than at Tuol Sleng prison in Phnom Penh. Tuol Sleng had originally been built as a secondary school during Sihanouk's regime. When the Khmer Rouge came to power, the buildings were converted to a prison -- or, more accurately, a torture and interrogation center.

Most of those incarcerated at Tuol Sleng were Khmer Rouge cadres who had fallen under suspicion during a series of purges. Many were women, and about 2,000 were children who had been taken to the prison along with their parents. Records from the prison indicate that at least 14,000 persons had been imprisoned there by January 1979.

Of those 14,000, there were seven known survivors.

Generally, Tuol Sleng held between 1000 and 1500 inmates at a time. Prisoners were brutally tortured in an attempt to extract "confessions" detailing counter-revolutionary plots masterminded by the Americans, the Soviets, or the Vietnamese. Among the preferred methods: pulling out fingernails, suffocating victims by temporary hanging, or crushing their nipples with pliers. Once a confession had been completed to Angkar's satisfaction, the prisoner was taken away to be killed. Prison records, which are incomplete, indicate that the highest single-day total of executions was on May 27, 1978, when 582 persons were sent to their death.

Death was coming to those in the countryside as well. In addition to the ever-present threat of execution, malnutrition and disease began to take a heavy toll on the population. The communal eating that Pol Pot had called for was instituted throughout most of the country by 1976. Seated together at long tables sheltered under thatch roofs, all of Angkar's slaves ate together. In prosperous regions, the food was generally rice, occasionally with some fish as well. In other areas, the only food was a watery rice soup. Only the Khmer Rouge ate their fill; others went hungry. In some areas people were allowed to forage for food when they were not working; they sometimes managed to catch fish or rabbits, and they could occasionally pick fruit. The less fortunate settled for field crabs, rats, lizards, or snakes. In still other areas, however, foraging for food was strictly forbidden. As men, women, and children starved to death, Angkar murdered people for the crime of trying to feed themselves. The welfare of the population often seemed completely irrelevant to the Khmer Rouge. One refugee recalled that, in order to kill the sparrows who ate the rice at harvest time, his work group was ordered to cut down the trees where the birds nested. "While people were dying of hunger a mile away, we were out chopping down fruit trees."

The main cause of the food shortages was not that insufficient rice was grown; the problem was that the rice was not distributed. Production quotas for each region were determined by the government in Phnom Penh, and local authorities were expected to send a set amount of rice to the central government. The quotas, however, were wildly unrealistic, and when they were not met local leaders were faced with a choice: send the amount requested to Phnom Penh and let their people starve, or admit failure to their superiors. Given the manner in which the regime dealt with failure and dissent, it is not surprising that many chose to pretend that the quota had been met.

The lack of food was compounded by a lack of medical care. Having emptied the hospitals during the evacuation of the cities, and having targeted doctors for elimination, the Khmer Rouge left the responsibility for treating the sick and injured in the hands of untrained young "revolutionaries" with predictably disastrous results. At the local level, cadres explained that only the methods of their ancestors would be used to treat illness; nothing would be taken from Western science. The leaders of the central government, like Pol Pot, Ieng Sary, and Khieu Samphan, were certainly well-educated enough to know that such folk remedies did not represent a viable substitute for modern medical science. But Cambodia could not produce modern pharmaceuticals domestically, and purchasing them abroad would have compromised the "purity" and "self-sufficiency" of the population.

Conditions worsened in 1977 and 1978. While there were fewer executions in 1976 and 1977 than there had been in 1975, the atmosphere was still one of brutality, repression, and fear. With a demoralized work force succumbing to disease and malnutrition, the country could no longer sustain itself. As their failure became apparent, the Khmer Rouge began to search for scapegoats. Intellectuals and persons with ties to the former government were still targets, but now the main focus shifted: Thousands of communist party members were imprisoned and executed as the Khmer Rouge began to devour their own ranks in a series of bloody purges. But internal purges were not enough. Without an external threat, the Khmer Rouge could not hope for internal support. Pol Pot had always manipulated the hatred of others to his own ends, and he would do so again now. Vietnam became the new enemy.

The Khmer Rouge had not forgotten their bitterness at the way the Vietnamese had given their own struggle against the American's precedence over the Cambodians communists' struggle against first Sihanouk and then Lon Nol. Ideology, too, was a factor; Vietnam was firmly rooted in the Soviet camp, while the Khmer Rouge were allied with the Chinese. Vietnam's own relations with China were particularly strained, mainly because of Vietnam's crackdown on her own ethnic Chinese. History, too, played a part, since ancient Vietnamese and Khmer empires had waged war on one another almost incessantly over the course of centuries. The single greatest factor, however, may have been the arrogance of the Khmer Rouge. Having withstood the American bombing and triumphed against Lon Nol, they had come to believe that they were invincible. Pol Pot capitalized on minor border disputes to claim that the Vietnamese had designs on Khmer territory. After a series of Khmer Rouge raids on villages inside Vietnam, heavy fighting broke our along the border in late 1977 -- ironically, at the same location where American forces had invaded some seven years earlier.

The fighting proved disastrous for the Cambodians, and Pol Pot concluded that his invincible army must surely have been infiltrated by Vietnamese spies. He responded with what may have been the most violent of the numerous purges of his bloody reign. The violence was directed primarily at party members in the Eastern Zone, the region bordering Vietnam.

A number of soldiers from the East managed to escape the purges by fleeing to Vietnam. There was unmistakable irony in their fate: Troops who had been fighting against the Vietnamese weeks earlier now ran to them for salvation.

One of the men who escaped to Vietnam was a division commander named Heng Samrin. His arrival was a blessing for the Vietnamese: they wanted to be rid of Pol Pot, but they needed another Cambodian to take his place. Heng Samrin was deemed suitable for the role, and on Christmas Day, 1978, an invasion force of 90,000 Vietnamese and 18,000 dissident Cambodians poured across the border into Cambodia.

The defense of Pol Pot's regime rested with an army of roughly 73,000 troops. Despised by the own people, confronted by a much better-equipped, brilliantly-led invasion force, the Khmer Rouge were routed with stunning ease. Within two weeks, the Vietnamese had captured Phnom Penh. The battered remnants of the Khmer Rouge retreated into the mountains and jungles along the Thai border.

Forced back against a wall, the previously xenophobic Khmer Rouge suddenly launched desperate pleas for assistance. Their greatest asset became the long-neglected Prince: Norodom Sihanouk was flown out of Cambodia and sent to the United Nations, where he gave an impassioned speech on behalf of the Khmer Rouge.

Within Cambodia, the Vietnamese -- long regarded with hatred and suspicion by Cambodians -- were suddenly seen as saviors. The darkest period in the nation's history had ended. In three-and-a-half years, out of a population of eight million people, more than two million people had died. And still, the misery was not over.

As the Khmer Rouge withdrew, they often confiscated and destroyed rice to prevent it from falling into the hands of the Vietnamese. In some areas, the Vietnamese, too, were accused of having confiscated much of the existing harvest. Much more simply rotted in the fields as liberated Cambodians abandoned their collectives en masse. Some returned to their homes from the days before the revolution. Hundreds of thousands of others fled toward Thailand. By October and November 1979, what had been a trickle of refugees became a torrent. The terrible mismanagement by the Khmer Rouge, the war and the dislocation had suddenly brought a new agony to Cambodia: Famine.

As the Khmer Rouge withdrew, they often confiscated and destroyed rice to prevent it from falling into the hands of the Vietnamese. In some areas, the Vietnamese, too, were accused of having confiscated much of the existing harvest. Much more simply rotted in the fields as liberated Cambodians abandoned their collectives en masse. Some returned to their homes from the days before the revolution. Hundreds of thousands of others fled toward Thailand. By October and November 1979, what had been a trickle of refugees became a torrent. The terrible mismanagement by the Khmer Rouge, the war and the dislocation had suddenly brought a new agony to Cambodia: Famine. Ultimately, much of the aid that did reach the interior of the country was distributed along the Thai border to Cambodians who carried it back into their own country in oxcarts and on rickety bicycles. While malnutrition continued to be a problem, by the end of 1979 the worst of the food shortages had passed.

Ultimately, much of the aid that did reach the interior of the country was distributed along the Thai border to Cambodians who carried it back into their own country in oxcarts and on rickety bicycles. While malnutrition continued to be a problem, by the end of 1979 the worst of the food shortages had passed. The idea that the people of Cambodia could have any use beyond that of a draft animal seemed to have never occurred to the Khmer Rouge. Anyone who offered advice to the Khmer Rouge was implicitly suggesting that Angkar's plan could be improved upon, and that perhaps Angkar was not infallible. Such a suggestion could easily lead to death. The Khmer Rouge saw intelligence not as a virtue, but as a threat. In many areas, educated persons were marked for execution as enemies of the state; many "new people" would later attribute their survival to having hidden their intelligence. College students, teachers, and doctors in particular were singled out as targets. Of approximately 270 doctors who remained in Cambodia after 1975, only about 40 survived Pol Pot's reign.

The idea that the people of Cambodia could have any use beyond that of a draft animal seemed to have never occurred to the Khmer Rouge. Anyone who offered advice to the Khmer Rouge was implicitly suggesting that Angkar's plan could be improved upon, and that perhaps Angkar was not infallible. Such a suggestion could easily lead to death. The Khmer Rouge saw intelligence not as a virtue, but as a threat. In many areas, educated persons were marked for execution as enemies of the state; many "new people" would later attribute their survival to having hidden their intelligence. College students, teachers, and doctors in particular were singled out as targets. Of approximately 270 doctors who remained in Cambodia after 1975, only about 40 survived Pol Pot's reign.

The banyan tree grows throughout Cambodia. It may reach a height of over 100 feet, and as it grows, new roots descend from its branches, pushing into the ground and forming new trunks. The roots grow relentlessly; many of the ancient temples of Angkor have toppled as these roots have become embedded in the cracks and crevices between their massive stones. A single tree might have dozens of trunks, and it is often impossible to tell which is the original.

The banyan tree grows throughout Cambodia. It may reach a height of over 100 feet, and as it grows, new roots descend from its branches, pushing into the ground and forming new trunks. The roots grow relentlessly; many of the ancient temples of Angkor have toppled as these roots have become embedded in the cracks and crevices between their massive stones. A single tree might have dozens of trunks, and it is often impossible to tell which is the original.